The Stillest Hour: Leaking a Highly Classified X-File

An interstellar voyage into the Fermi Paradox, the Great Filter, and the big cosmic question: where are all the aliens out there?

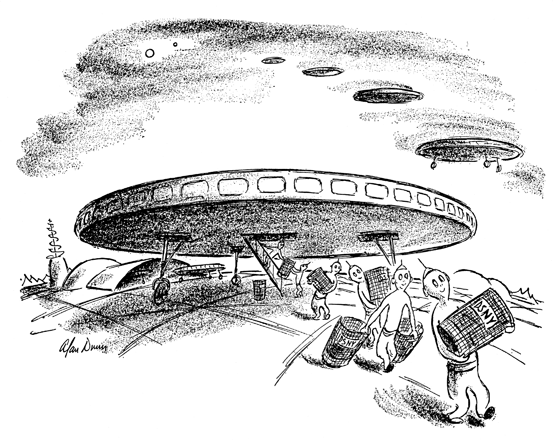

Let’s begin with a paradox that first arose in 1950, as four nuclear physicists were discussing increasing reports of UFO sightings and missing trashcans all over the United States. Inventor of the first nuclear reactor Enrico Fermi jokingly suggested that extraterrestrial aliens could be responsible for both the UFOs and the abducted garbage. Although none of the four physicists actually took the strange reports of flying saucers seriously, they did prompt Fermi to ask a decisive question: “where is everybody?” Fermi’s reasoning was as follows: given that the age of the Milky Way galaxy at approximately 13.6 billion years is much vaster than its size at roughly 100,000 light years in diameter, there has already been more than enough time for any self-replicating DNA hatched on one of the millions of exoplanets to evolve into intelligent life, develop space travel technology, and transmit its existence to earth. Unless humanity is an extremely improbable exception or the aliens are already among us in the guise of UFOs, this raises what has come to be known as the “Fermi Paradox”: why haven’t we observed any signs of highly probable alien life yet? Where are all the extraterrestrial billionaires visiting us from other worlds? Based on his correspondence 35 years later with Herbert York, one of the four original physicists privy to the conversation, Eric Jones sums up the paradox in this way:

York believes that Fermi was somewhat more expansive and “followed up with a series of calculations on the probability of earth-like planets, the probability of life given on earth, the probability of humans given life, the likely rise and duration of high technology, and so on. He concluded on the basis of such calculations that we ought to have been visited long ago and many times over. As I recall, he went on to conclude that the reason we hadn’t been visited might be that interstellar travel is impossible, or, if it is possible, always judged to be not worth the effort, or technological civilization doesn’t last long enough for it to happen.”[1]

Fermi’s Paradox thus emerges because the complete lack of any surefire evidence of life other than on earth in our observable light cone seems to contradict the extreme probability that many extraterrestrial civilisations ought to exist and even to have already developed the capacity to colonize the nether regions of the cosmos. Fermi’s Paradox is a theory-bit, a joke that makes itself real.

In 1998, economist and AI theorist Robin Hanson proposed what he termed the “Great Filter” as an answer to the Fermi Paradox: something is preventing life from advancing to the point where it can colonize the starry heavens, a kind of cosmic Tinder filter swiping left on life’s mirror reflection. As Hanson puts it:

The fact that space near us seems dead now tells us that any given piece of dead matter faces an astronomically low chance of begetting such a future. There thus exists a great filter between death and expanding lasting life, and humanity faces the ominous question: how far along this filter are we?[2]

Fermi’s Paradox is the paradox of an absence: not something mysterious we can see that needs elucidating, but something we don’t see which nonetheless summons us to imagine it. Much as the OG modern philosopher Immanuel Kant proposed the concept of “the transcendental” as the invisible, yet necessary conditions of possibility for what we can empirically experience, so is the Great Filter the invisible, yet necessary condition of possibility for what we do see—which is precisely nothing but the stellar void.

A diverse and sometimes absurd array of candidates has been proposed as to just what the Great Filter might be. In his 2018 book The Great Silence: The Science and Philosophy of Fermi’s Paradox, Milan M. Ćirković classifies the myriad solutions into four general types.[3] Firstly, “solipsistic” or “they are here” solutions simply disavow outright that the Fermi Paradox even exists because we can allegedly observe signs of alien life already among us, be they pyramids and other complex sphinxical structures that can apparently be explained only by way of extraterrestrial architects or dubious photos and blurry radar scans of UFOs. In short, the solipsistic solution evokes TFW NO GF (Great Filter). A more recent twist on the solipsistic solution is “the simulation hypothesis.” Causing a stoned Joe Rogan much confusion when Nick Bostrom tried to explain it to him on his podcast, the simulation hypothesis proposes that we are living in a virtual reality simulation designed by intelligent beings. Although believers in UFOs transporting alien Jeff Bezoses think they are courageously affirming the unknown, they are in fact repressing Fermi’s even more confronting mystery of the sterile colour out of space. What we can’t see in shoddy photographs of UFOs—namely any direct and reliable evidence of E.T.s far from home—is much more alienating than what we can see.

Secondly, “rare earth” or “they did not evolve” solutions argue that the Fermi Paradox isn’t as paradoxical as it seems—provided that intelligent life like our own is in fact an extremely rare and contingent occurrence in the universe, rather than a probable outcome around which the fundamental laws of physics and evolutionary biology almost universally converge. There are several key milestones along the way to the evolution of intelligent life like us: the right star system; RNA; simple prokaryotic single-cell life; complex archaeatic and eukaryotic single-cell life; sexual reproduction; multi-cellular life; tool using animals with big brains; modern homo sapiens; and space travel technology. If one or more of these steps is highly improbable, then the so-called Fermi “Paradox” is less a paradox than exactly what we should expect to see. As evolutionary biologist Stephen J. Gould observes, “wind back the tape of life to the early days of the Burgess Shale; let it play again from an identical starting point, and the chance becomes vanishingly small that anything like human intelligence would grace the replay.”[4]

Thirdly, “logistical” or “they have been prevented from coming and developing yet” solutions hold that the vast majority of intelligent civilisations typically decide that the most rational course of action is not to colonize the galaxy and thereby communicate their presence to other civilisations despite the seduction of immense resources in other star systems. One possible explanation for this—and one explored in science fiction writer Liu Cixin’s The Three Body Problem and The Dark Forest novels—is that alien races are simply too smart to expose their location to potentially hostile competitors in a kind of cosmic trigger warning. Whereas humanity appears to go against the basic game-theoretical tactics of warfare by loudly announcing our location and what traumas trigger us, more intelligent species capable of spacefaring would refrain from beaming their existence to other species whose intentions and force of strength they know nothing about. It is not for nothing that Fermi conceived of his paradox in a dialogue among nuclear physicists in the wake of the second world war and at the advent of the cold war.

Another logistical solution is that most advanced civilisations ultimately converge around a certain stage of development where they choose to turn inward and recursively self-improve rather than expand outward and explore the galaxy. As per the typical sci-fi depiction of futuristic megacities—like the vast urban “sprawl” in William Gibson’s Neuromancer, smeared out in space and teeming with space hubs to travel even further outward—we are accustomed to imagining that civilisations become ever more extroverted with each great technological leap forward. But if real-world advances in computer chips as they get increasingly smaller as well as the latest frontier of cyberspace tell us anything, it’s that civilisations tend to withdraw inward and cultivate themselves like meditating monks as they progress. It would seem that the technological singularity is less an “intelligence explosion” as some have called it and more an intelligence implosion.

Finally, “neocatastrophic” or “they have been destroyed or transformed” solutions hypothesise that the Great Filter does not prevent life as such from emerging and developing, but only from enduring beyond a certain advanced stage of civilisation. As Nick Bostrom encapsulates it:

To constitute an effective Great Filter, we hypothesise a terminal global cataclysm: an existential catastrophe. An existential risk is one where an adverse outcome would annihilate Earth-originating life or permanently and drastically curtail its potential for future development. We can identify a number of potential existential risks: nuclear war fought with stockpiles much greater than those that exist today (maybe resulting from future arms races); a genetically engineered superbug; environmental disaster; asteroid impact; wars or terrorist acts committed with powerful future weapons, perhaps based on advanced forms of nanotechnology; superintelligent general artificial intelligence with destructive goals; high-energy physics experiments; a permanent global Brave-New-World-like totalitarian regime protected from revolution by new surveillance and mind control technologies.[5]

To break that down a bit, one version of the neocatastrophic solution to which we may ourselves have already succumbed—at least until private space companies like SpaceX came along—is that every civilization ultimately converges around a totalitarian form of governance that for one reason or another represses far-flung space exploration. If we look to the history of space travel that started out so promisingly with the Soviets’ 1957 Sputnik satellite launch and the Yankees’ 1969 Apollo moon landing, it was not long before both superpowers’ space policies shifted to sending men back to the moon only to have them return to earth, with all further dreams of establishing a moon base, colonizing Mars and Venus, and becoming a multi-planetary species put on the backburner. For all its praise of free market liberalism, as far as space was concerned, the US simply adopted the technocratic model from both its state socialist rival and the Third Reich from which it recruited its chief rocket scientists. Throughout the 20th century, war communism was the only policy ever adopted in outer space. Perhaps the most plausible candidate for the Great Filter that explains why we haven’t observed any other intelligent life out there is that at a certain stage in their respective histories all civilizations get sucked into the infinite blackhole of the State. It would seem that it is just as hard to convince a bloated state bureaucracy with allegedly better things to do on earth to fund quasi-noumenal space exploration as it is to convince a Hegelian that things in themselves exist outside their own inflated egos. If earth is the cradle of humanity, then Project Apollo is humanity’s Lacanian mirror stage. As much as we might stray from Mother Earth, humanity will always return like the mummy’s boy it is.

Another neocatastrophic solution holds that there are just way too many natural megadisasters that in all likelihood impede the survival of species in the long run, from asteroid collisions and exploding super volcanoes to planetary-wide ice ages and runaway global warming. It would seem that mother earth is not a Gaia but a Medea, strangling her children in the mass extinction events that have already scarred the earth’s fossil record beyond cosmetic repair. Another version proposes that every civilization eventually develops the technology that leads to its destruction, whether it’s nuclear weapons, lab-made viruses, anthropogenic climate change, Skynet style AI, or runaway globalised capitalism. Again, it is not for nothing that Fermi first conceived of the paradox in between the bloodshed of the second world war and the cold war.

What makes the neocatastrophic solution particularly perturbing is that we may very well be approaching the technological stage of development that triggers the Great Filter. The Great Filter would thus not only be an account of the absence of extant alien civilisations elsewhere, but also a time machine allowing us to travel to the future fate of our species’ collective suicide. This is what Bostrom is getting at when he says:

Many people would also find it heartening to learn that we are not entirely alone in this vast cold cosmos.

But I hope that our Mars probes will discover nothing. It would be good news if we find Mars to be completely sterile. Dead rocks and lifeless sands would lift my spirits.[6]

Contrary to The X-Files’ Agent Mulder, Bostrom wants to unbelieve. His reasoning is that the Great Filter has either already happened or it is yet to take effect. If it has already come to pass, then we are the one lucky civilisation that has managed to survive its genocidal wrath against all odds. If we do find other extant lifeforms, however, it makes it more likely that the Great Filter is still to come. And indeed, the more lifeforms we find, the ever more likely it is that the Great Filter is still on its way. Bostrom thus concludes:

Consider the implications of discovering that life had evolved independently on Mars (or some other planet in our solar system). That discovery would suggest that the emergence of life is not a very improbable event. If it happened independently twice here in our own back yard, it must surely have happened millions of times across the galaxy. This would mean that the Great Filter is less likely to occur in the early life of planets and is therefore more likely still to come…[7]

The more life we find in the universe, the more statistically fucked we become. To go out with a whimper by way of my beloved philosophical soulmate Nietzsche’s rumination on a certain cosmic silence:

And just believe me, friend Infernal Racket! The greatest events—these are not our loudest, but our stillest hours.

Not around the inventors of new noise does the world revolve, but around the inventors of new values; inaudibly it revolves.[8]

Originally written in 2021 for an invited lecture at the Centre for Contemporary Photography, which was cancelled due to a COVID-19 lockdown.

[1] Eric M. Jones, “‘Where is Everybody?’ An Account of Fermi’s Question” (Los Alamos: Los Alamos National Laboratory, 1985), 3.

[2] Robin Hanson, “The Great Filter—Are We Almost Past it?”, George Mason University, September 15, 1998, accessed July 3, 2021, https://mason.gmu.edu/~rhanson/greatfilter.html.

[3] Milan M. Ćirković, The Great Silence: The Science and Philosophy of Fermi’s Paradox (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2018).

[4] Stephen Jay Gould, Wonderful Life: The Burgess Shale and the Nature of History (London: W. W. Norton and Company, 1989), 14.

[5] Nick Bostrom, “Where Are They? Why I Hope the Search for Extraterrestrial Life Finds Nothing,” Nick Bostrom, 2008, accessed July 3, 2021, https://nickbostrom.com/papers/where-are-they/.

[6] Bostrom, “Where Are They?”

[7] Bostrom, “Where Are They?”

[8] Bostrom, “Where Are They?”

There're quite a few paradigms on the Fermi Paradox.

I personally like the ancient civilization hypothesis, being that humanity escaped from some great alien war. We decided to hide out on our planet, eventually forgetting that we once were gods, whilst imposing some protective measures to keep us from observing or being observed.