Curtis Yarvin Contra Mencius Moldbug (Part 2)

An intro to Yarvin’s political philosophy as he laid it out writing under the pseudonym Mencius Moldbug, as well as a critique of a conceptual vibe shift in his recent works written under his own name

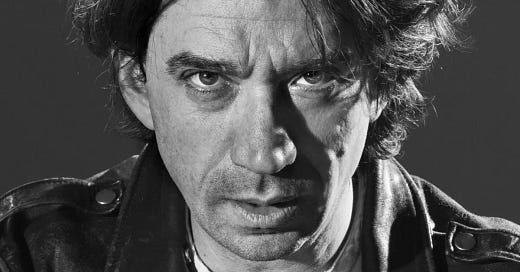

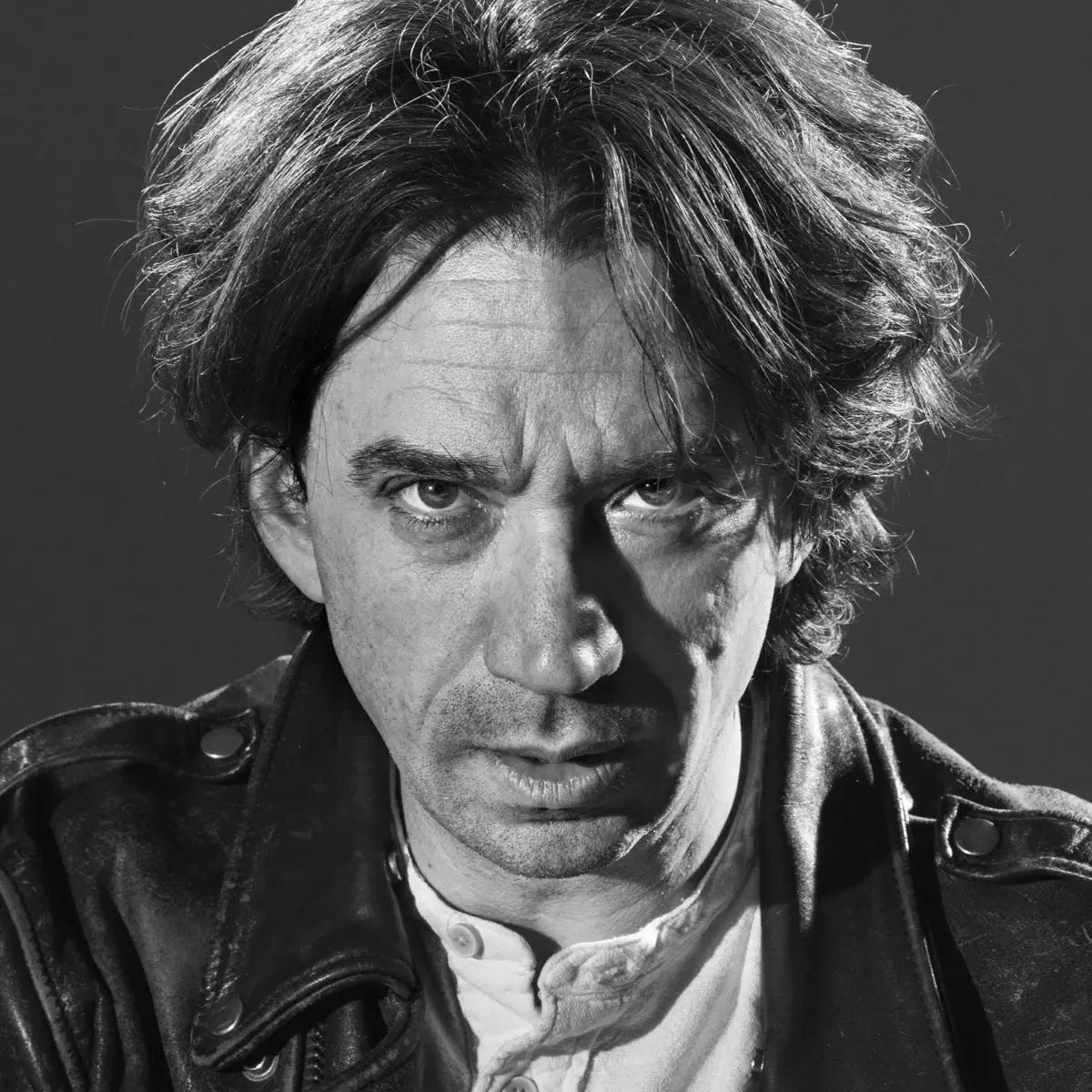

Since 2020, Moldbug has ripped off his ominous Ghostface mask to write under his own name Curtis Yarvin on his substack Gray Mirror. With his influence among Silicon Valley tech bros and the Trump administration having burgeoned in recent times, Yarvin has become to the neoreactionary right what Darth Sidious is to the Sith Lords. So it’s no surprise that, in the wake of Trump’s second election victory when everyone was desperately looking for quick answers and easy scapegoats, Darth Yarvin was interviewed by nothing less than one of the Cathedral’s great pillars, The New York Times. This interview provides a pretty decent summary of what I would describe as a conceptual vibe shift in Yarvin’s recent political thought. Having outlined Yarvin’s original neocameralist political philosophy in this essay’s previous instalment, I now want to outline this vibe shift before showing how the new Yarvin can be immanently critiqued by way of the old Yarvin or Moldbug.

On first impressions, it can certainly seem like the new Yarvin is still the same old guy you know and probably hate. As he explains in the New York Times interview, he still maintains that his “number one” principle is that “having an effective government and an efficient government is better for people’s lives.”[1] Equally, he still believes that “democracy is not a good system of government” for achieving those ends.[2] On closer examination, however, we no longer find him emphasizing that good governance is most efficiently selected for through a patchwork of competing sovcorps. Instead, he contends that sound government policy can only be devised by lawyers, professors, and other technocrats with the requisite expertise. In other words, those who govern should not be democratically elected but a meritocratic aristocracy of “wise experts”:

When you basically want to say democracy is not a good system of government, just bridge that immediately to saying populism is not a good system of government. And then you’ll be like, yes, of course. Actually, policy and law should be set by wise experts and people in the courts and lawyers and professors and so forth. Then you’ll realize that what you’re actually endorsing is aristocracy rather than democracy.[3]

When asked “why having a strong-man figure would be better for people’s lives,” the “best answer” Yarvin can give is to point out that everything which works in our everyday lives is already made and operated by an absolute monarchy.[4] For instance, our iPhones and MacBooks are made by Apple. But Apple is not run like a democracy where all its employees get an equal say as to what they should produce and how they should go about making it. This is rather decided by its CEO and/or board of directors ordering the technical team and everyone else around:

I think that the best answer, when I ask people to answer that question, I ask them to look around the room and basically point out everything in the room that was made by a monarchy. Because these things that we call companies are actually like monarchies. And then you’re looking around yourself and you see, for example, a laptop. And that laptop was made by Apple, which is a monarchy.[5]

Show Yarvin any everyday product that works today and he will show you the monarchy that made it.

Not unlike a philosopher working up a sweat over their trolley problems, Yarvin proffers a simple thought experiment that, as we shall see, rather misses the point. If the US government were to nationalize Apple so that “your MacBook Pro was made by the California Department of Computing,” it would be difficult to say with a straight face that the product would in any way improve.[6] But if Elon Musk’s SpaceX was allowed to privatize a government bureau like NASA, it would all but assure that we get way “more cool space shit”:

If you compare NASA to SpaceX, that’s a fine example of, actually, all of the principles that I’ve been describing because NASA was once as efficient as SpaceX. So if you basically say, OK, at a very abstract level, forget the rest of the government. Elon, go and fix NASA. The goal of NASA is to give us cool space shit. We feel like we’re not getting enough cool space shit. You have $25 billion a year. Go and do cool space shit. I think you would get a lot more cool space shit under that principle.[7]

While one might object that SpaceX is a rather exceptional company, Yarvin rebuts that you could simply hand over government services to any of the Fortune 500 companies at random and they would pretty much all do a better job of running them:

I think that if you took any of the Fortune 500 CEOs, some of them are good, some of them are bad. But the overall quality, just pick one at random, and put him or her in charge of Washington, and I think you’d get something much, much better than what’s there. It doesn’t have to be Elon Musk. The median performance is so much better.[8]

It would seem that neocameralism is already here, it’s just not evenly distributed yet.

One might be tempted to protest that making iPhones is one thing while running a country puts much more at stake. And yet, Yarvin stresses, the more critical the service at hand, the more necessary one-man rule seems to be:

One of the things about monarchy that’s been known for quite some time—and again, even in very, very anti-monarchial regimes and periods, an exception is made for this—is that a ship always has a captain. An airplane always has a captain. Basically, in any very safety-critical environment … you should have someone in charge.[9]

If the one-man rule principle holds true in safety-critical situations like flying a plane or performing surgery, it should be even more the case for running a government in whose hands whole masses of people’s lives are at stake. Yarvin gives the example of a future SpaceX colony on Mars. Rejecting Elon Musk’s speculation that the colony would be run like a democracy, he insists that how the oxygen tanks are to be replenished and all the other safety-critical governance decisions could hardly be left to a democratic vote. If the Mars colony is going to survive, let alone expand and flourish, they can only be decided by the very few with the relevant expertise:

Are the citizens of the Mars colony going to vote on how to replenish the oxygen supply or whatever? No, of course not. The Mars colony that Elon establishes will be a subsidiary of SpaceX, and it will have someone in charge. And it will have a command hierarchy, just like SpaceX does. And so I’m like, Elon, when you say that this should be a democracy, what are the people voting on?[10]

Perhaps Yarvin’s most hard fork disagreement with traditional libertarians is that they are wrong to conceive of capitalism as maximizing freedom. On the contrary, capitalist corporations are actually run internally like monarchies understood as “completely top-down command units.”[11] It is this absolute power purportedly possessed by capitalist corporations and monarchical governments alike that Yarvin ultimately believes makes them so effective.

What would the Moldbug of Unqualified Reservations make of all this? If he is honest with himself, I think he would have to say, “I Miss the Old Yarvin.” More precisely, I think he would say that the new Yarvin has made a subtle but decisive shift from identifying the patchwork as the driving engine for capitalism’s unreasonable effectiveness to focusing on the top-down corporate command structure. In other words, he has shifted from looking at things from the outside in to looking at things from the inside out.

In this essay’s first part, we saw Moldbug contend that what makes a capitalist corporation—and what would presumably make a sovcorp—the best-selling optimization algorithm since natural selection is that it does not exist in a vacuum, but is embedded in a patchwork with other corps. This obliges all of them to compete with each other to provide better goods and services if they are to attract customers—or citizens—and accrue greater profits. By contrast, the new Yarvin holds that what makes a capitalist corporation or monarchical government work is that its CEO-king has the absolute power to run the company or rule over his fiefdom however he sees fit. But this elides how the effectiveness of capitalist corporations does not stem from the CEO’s absolute power to do whatever they want. It rather stems from the way each corporation is forced to improve because they exist in a market or patchwork with other rival corporations.

More precisely, the new Yarvin overlooks the two fundamental reasons why capitalism’s efficiency can be attributed to its competitive dynamics. Firstly, competition compels corporations to invest the vast bulk of their profits into improving goods and services—along with the means of producing them—in order to keep up with their rivals. If a single corporation ever had truly absolute power to do actual king shit, then it would have no need to invest its profits in improving production rather than in the hedonistic consumption of, say, champagne, escorts, and Scarface levels of coke. It is not absolute power, then, but competitive pressures that obliges capitalist corporations to relentlessly optimize. What’s more, competition provides a kind of epistemology for objectively calculating which corporations demonstrably prove to be more effective than others by comparing the fruits of their various harvests with one another. Beyond our gut hunches, stabs in the dark, and biases, we are only able to impartially determine which corporations prove more successful than others by making comparisons as communicated through the competitive price signals of lower production costs, cheaper goods, and fatter profits. An all-powerful monopoly without any competitors would thus not stay one for long, because it would lack the epistemic means of measuring whether an improvement has really taken place by way of comparison with its rivals. Putting two and two together, then, it is only a competitive patchwork that provides corporations with both the incentive to incessantly improve and the epistemic means of determining genuine improvements. Conversely, a single corporation with absolute power would actually undermine these two transcendental conditions of possibility enabling capitalist corporations to thrive. In imagining that simply having absolute power would be enough for a CEO-king to know how to most effectively run a corporation or even manage the government, Yarvin is closer to a card-carrying commie extolling the virtues of centralized rational planning than he is to an Austrian economist outsourcing work on such hard problems to the invisible hand.

From the old Yarvin’s perspective, it is a grave obfuscation for the new Yarvin to claim that capitalist corporations and monarchical governments work because they have absolute power. Seeing as each capitalist corporation or sovcorp must compete in a patchwork with other corps, they cannot really be said to have complete sovereignty. It is rather the patchwork of corps outside of any individual corp that is really controlling what they all do as it compels them to provide better goods and services. While the CEO-king or queen might be able to choose between more moves than a pawn, they are still subject to the rules of the game before which their decrees mean little more than the prayers of the lowliest peasant. Only the patchwork itself is truly sovereign. Only the patchwork is king. Far from corps being successful because they have absolute power, they are successful precisely because there are severe limits to their power—that is, because they cannot do whatever they want but must perpetually pump out better goods and services if they are to survive. Who would have thought that “absolute power” came with so many constraints?

We could thus say that the new Yarvin is committing an anthropomorthization of what actually makes capitalism so dynamic: that is, he mistakes its impersonal selection mechanism for its human face. The only reason I can think of to make any conceptual sense of this vibe shift is to imagine that the new Yarvin is himself the merely tactical human face or seamless Mission Impossible mask disguising the fittingly pseudonymous Moldbug’s impersonal patchwork. But when a disguise has you doubting what your ends were to begin with, it is time to take off the mask.

[1] Curtis Yarvin quoted in David Marchese, “The Interview: Curtis Yarvin Says Democracy is Done. Powerful Conservatives are Listening,” The New York Times, January 18, 2025, accessed January 20, 2025, https://www.nytimes.com/2025/01/18/magazine/curtis-yarvin-interview.html.

[2] Yarvin, “Interview.”

[3] Yarvin, “Interview.”

[4] Marchese and Yarvin, “Interview.”

[5] Yarvin, “Interview.”

[6] Yarvin, “Interview.”

[7] Yarvin, “Interview.”

[8] Yarvin, “Interview.”

[9] Yarvin, “Interview.”

[10] Yarvin, “Interview.”

[11] Yarvin, “Interview.”

Good assessment and critique of Yarvin (in this post and the last one). It's important to remember that the new UR site gives only half the story of the blog, since it omits the high-quality comments that were made on the original Blogspot posts. After a while, Yarvin ceased to read or respond to these comments (a bad habit he has retained into the present day), but this was not the case in the first two years when he was working out neocameralism and patchwork.

If you search the old site (http://unqualified-reservations.blogspot.com) to find the early posts on these topics, and use the Wayback Machine to restore them, you will see that the more erudite commenters – notably the libertarian Nick Szabo – made some pretty strong objections to the whole notion of governance-for-profit. Some of the debates got technical, but the gist of their objection was that the rulers of a sovereign state would have a totally different set of incentives from the managers of a private corporation. This post has one of the less heated threads on the subject:

http://web.archive.org/web/20101016022302/http://unqualified-reservations.blogspot.com/2007/05/limited-government-as-antipropertarian.html

Although Yarvin defended himself at the time, he never really addressed the objections satisfactorily (nor did he give good reasons for rejecting the Burnhamite 'managerial revolution' thesis, according to which there is no essential difference between corporate managers and government bureaucrats), and as time went on he simply stopped talking about the governance-for-profit element of his scheme. In later UR and his current writings, all that is left of it (other than practical details of implementation such as the orderly coup d'etat, techno-assisted surveillance state, non-metallic hard money, etc.) is a much more simplistic version, in which the absolute power of the CEO-monarch is relied upon to keep the bureaucratic class from getting out of control. This is hardly convincing, since as Mosca said "all government is oligarchy", and without governance-for-profit the additional incentives for restraining that oligarchy are all gone.

Yarvin was right to be influenced by the early criticisms, but he was wrong to simply attenuate his theory without explaining his reasons, and continue serving up the inadequate remnant to his audience without acknowledging the need to go back to the drawing board. Yet most of his readers, unlike you, do not even seem to have noticed the problem.

From “from Mises to Carlyle”

“To achieve spontaneous order: first, achieve ordinary, down-to-earth, nonspontaneous order. Then, wait a while. Then, start to relax.

Here is the Carlylean roadmap for the Misesian goal. Spontaneous order, also known as freedom, is the highest level of a political pyramid of needs. These needs are: peace, security, law, and freedom. To advance order, always work for the next step—without skipping steps. In a state of war, advance toward peace; in a state of insecurity, advance toward security; in a state of security, advance toward law; in a state of law, advance toward freedom.”

https://www.unqualified-reservations.org/2010/02/from-mises-to-carlyle-my-sick-journey/